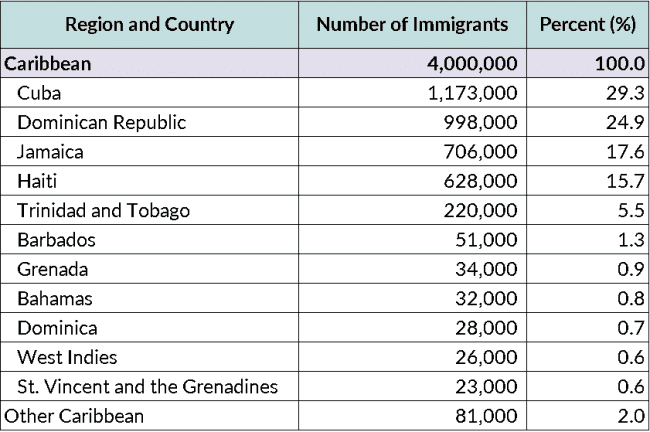

In 2014, approximately 4 million immigrants from the Caribbean resided in the United States, accounting for 9 percent of the nation’s 42.4 million immigrants. More than 90 percent of Caribbean immigrants came from five countries: Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Haiti, and Trinidad and Tobago (see Table 1). Immigrants from the Caribbean vary in their skill levels, racial composition, language background, as well as migration pathways to the United States, depending on origin country and period of arrival.

Despite the geographic proximity of the Caribbean region, large-scale voluntary migration to the United States did not begin until the early 20th century. Prior to that, the region was primarily a destination for European colonizers and persons from sub-Saharan Africa and Asia brought as slaves or servants. The abolition of slavery in Caribbean countries in the 19th century created a large pool of free labor and potential emigrants. Foreign corporations (mostly based in the United Kingdom and France) recruited former slaves as workers to labor-scarce colonies. Such movements were initially restricted inside the Caribbean region; however, by the early 1900s, the United States had become a major destination for Caribbean migrants due to the improved economic situation there and an increasing U.S. presence in the region. With the notable exception of Jamaica, all major Caribbean island nations were under direct U.S. political control at some point. Most Caribbean immigrants to the United States prior to 1960 were labor migrants, including agricultural workers who came through the British West Indies guest worker program in the mid-1940s, but some were political exiles from Cuba.

Table 1. Distribution of Caribbean Immigrants by Country of Birth, 2014

Source: MPI tabulation of data from U.S. Census Bureau 2014 American Community Survey (ACS).

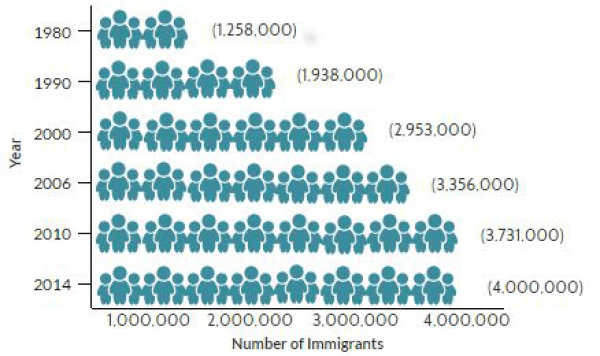

The 1960s marked the beginning of the acceleration of Caribbean immigration. Starting with fewer than 200,000 in 1960, the Caribbean immigrant population grew significantly over the next couple decades. The population increased 248 percent in the 1960s (to 675,000), 86 percent in the 1970s (to 1.3 million), 54 percent in the 1980s (1.9 million), 52 percent in 1990s (3 million), and another 35 percent between 2000 and 2014 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Caribbean Immigrant Population in the United States, 1980-2014

Sources: Data from U.S. Census Bureau 2006, 2010, and 2014 ACS; and Campbell J. Gibson and Kay Jung, “Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850-2000” (Working Paper no. 81, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, February 2006), available online.

Unlike flows from other parts of the world, the uptick in Caribbean immigration was not prompted by the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act because migration from the Western Hemisphere had not been subject to the national origin quotas set in 1921 and 1924. Instead, the growth had to do with circumstances specific to each country. Migration from Jamaica and other former British colonies was driven by immigration restrictions set by the United Kingdom and the simultaneous recruitment by the United States of English-speaking workers of varying skill levels (from rural laborers in agriculture or construction to nurses). Flows from Cuba, Haiti, and to a lesser extent the Dominican Republic, were first driven by the political instability at home, prompting members of the elite and skilled professionals to emigrate. As economic conditions deteriorated, these migration flows increased and grew to include other social groups. Thus, while the upper middle class represented a sizable portion of immigrants from Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic in the 1960s, it declined as a share later. In contrast, a relatively high share of Jamaican immigrants to the United States has consistently been skilled professionals.

Cuban immigrants receive unique treatment under current U.S. immigration law. The Cuban Adjustment Act (CAA) in 1966 and the 1994 and 1995 U.S.-Cuba Migration Accords set the groundwork for what eventually became known as the “wet foot, dry foot” policy. Under this policy, which is still in effect, Cubans who reach U.S. soil are fast-tracked for U.S. permanent residence and have the right to receive public assistance as refugees, while those intercepted at sea are returned to Cuba. President Obama’s announcement of the restoration of full diplomatic relations with Cuba in December 2014 created uncertainty about the future of the policy and inadvertently prompted a significant increase in migration flows from Cuba. In fiscal year (FY) 2015, about 43,200 Cubans entered the United States, a 78 percent increase from 24,300 the previous year, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) data released to the Pew Research Center. During the first ten month of FY 2016, CBP recorded 46,600 Cuban entries. These flows are significantly higher than in prior years; for instance, an average of 10,000 Cubans entered the United States annually between FY 2005 and FY 2010.

Historically, most Cubans attempted to reach the United States by crossing the Florida Straits. More recent data suggest that the routes have shifted, or at least diversified: The majority of Cuban arrivals in FY 2015 (66 percent) and the first 10 months of FY 2016 (64 percent) entered by land through CBP’s Laredo Sector in Texas. Many of these migrants transited through a number of Latin American countries (e.g., Ecuador, Columbia, Costa Rico, Nicaragua, and Mexico), although recent visa and other policy changes in these countries have made this route more difficult.

One distinct feature of Caribbean immigration is its racial diversity. Although roughly half of Caribbean immigrants identified themselves as black, this share varied by country of origin: More than 90 percent of immigrants from Jamaica and Haiti self-identified as black, compared to only 3 percent and 14 percent of immigrants from Cuba and the Dominic Republic, respectively.

The increased Caribbean migration flows after the 1960s also included a significant number of unauthorized immigrants, some of whom arrived illegally by boat while others arrived legally and subsequently overstayed their visas. The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimates that approximately 232,000 unauthorized Caribbean immigrants resided in the United States during the 2010-14 period, representing 2 percent of the total 11 million unauthorized immigrants. The Dominican Republic (98,000), Jamaica (59,000), and Haiti (7,000) are the leading origin countries of unauthorized immigrants from this region.

The United States is the top destination for Caribbean emigrants, accounting for more than 60 percent of the 6 million Caribbean emigrants worldwide. It is followed by Canada (365,000), the Dominican Republic (334,000), and Spain (280,000), according to mid-2015 estimates from the United Nations Population Division. Click here to view an interactive map showing where migrants from each Caribbean country settle worldwide.

On average, most Caribbean immigrants obtain lawful permanent residence in the United States (also known as receiving a green card) through three main channels: They qualify as immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, through family-sponsored preferences, or as refugees and asylees. Compared to the total foreign-born population, Caribbean immigrants are less likely to be Limited English Proficient (LEP), but have lower educational attainment, lower median incomes, and higher poverty rates.

Using data from the U.S. Census Bureau (the most recent 2014 American Community Survey [ACS] as well as pooled 2010-14 ACS data), the Department of Homeland Security Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, and World Bank annual remittance data, this Spotlight provides information on the Caribbean immigrant population in the United States, focusing on its size, geographic distribution, and socioeconomic characteristics.

Note: Detailed socioeconomic characteristics are available only for immigrants from the Caribbean overall and those from Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago due to sample size limitations.

Click on the bullet points below for more information:

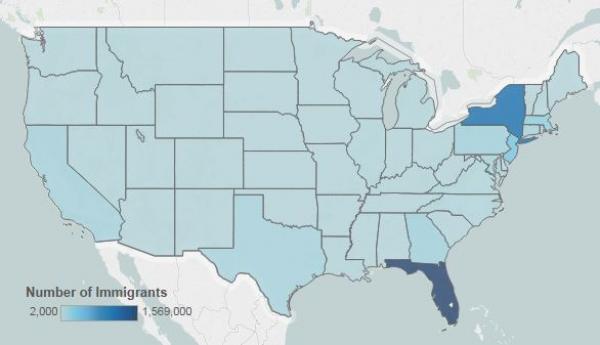

Distribution by State and Key Cities

Caribbean immigrants were heavily concentrated in Florida (40 percent), New York (28 percent), and to a less extent, New Jersey (8 percent), according to 2010-14 ACS data. The top four counties with Caribbean immigrants were Miami-Dade County in Florida, Kings County in New York, Broward County in Florida, and Bronx County in New York. Together, these counties represented 41 percent of the Caribbean immigrant population in the United States.

Figure 2. Top Destination States for Caribbean Immigrants in the United States, 2010-14

Note: Pooled 2010-14 ACS data were used to get statistically valid estimates at the state and metropolitan statistical area levels for smaller-population geographies.

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulation of data from U.S. Census Bureau pooled 2010-14 ACS.

Click here for an interactive map that shows the geographic distribution of immigrants by state and county. Select the Caribbean region or individual Caribbean countries from the dropdown menu to see which states and counties have the highest distributions of Caribbean immigrants.

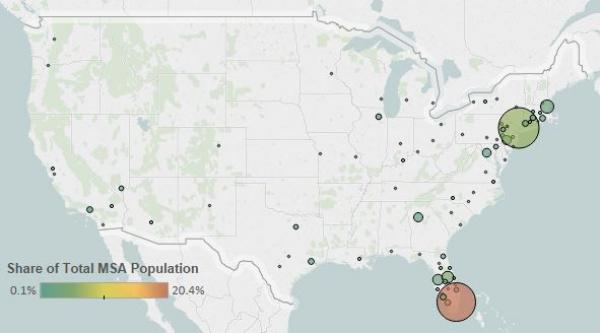

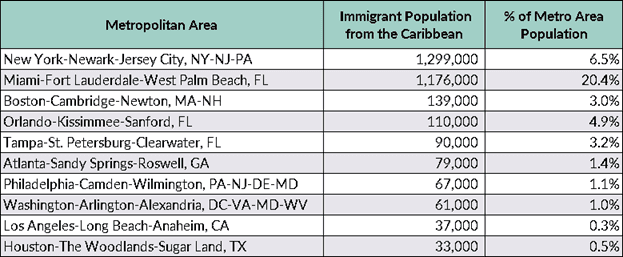

In the 2010-14 period, the U.S. cities with the greatest number of Caribbean immigrants were the New York City and Miami metropolitan areas. These two metropolitan areas accounted for 64 percent of Caribbean immigrants in the United States.

Figure 3. Top Metropolitan Area Destinations for Caribbean Immigrants in the United States, 2010-14

Note: Pooled 2010-14 ACS data were used to get statistically valid estimates at the state and metropolitan statistical area levels for smaller-population geographies.

Source: MPI tabulation of data from U.S. Census Bureau pooled 2010-14 ACS.

Table 2. Top Concentrations by Metropolitan Area for the Foreign Born from the Caribbean, 2010-14

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau pooled 2010-14 ACS.

Click here for an interactive map that highlights the metropolitan areas with the highest concentrations of immigrants. Select the Caribbean region or individual Caribbean countries from the dropdown menu to see which metropolitan areas have the highest concentrations of Caribbean immigrants.

English Proficiency

Caribbean immigrants (ages 5 and older) were less likely to be LEP (43 percent) than the overall foreign-born population (50 percent). At the same time, 31 percent of Caribbean immigrants spoke only English at home, nearly twice the share (16 percent) for all immigrants. However, LEP rates vary by country of origin. The majority of immigrants from English-speaking Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago spoke English only (92 percent and 96 percent, respectively). In contrast, immigrants from Spanish-speaking Cuba and the Dominican Republic had high LEP rates (62 percent and 64 percent, respectively).

Note: Limited English proficiency refers to those who indicated on the ACS questionnaire that they spoke English less than “very well.”

Age, Education, and Employment

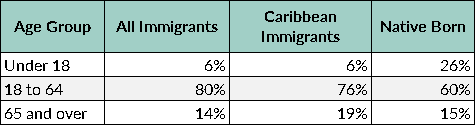

The Caribbean immigrant population was older than both the overall immigrant and native-born population. The median age of Caribbean immigrants was 48 years, compared to 44 for all foreign born and 36 for the native born. In 2014, 76 percent of Caribbean immigrants were of working age (18 to 64), compared to 80 percent of all immigrants and 60 percent of the native-born population (see Table 2). Median age also varies by origin country; immigrants from Cuba (52 years old), Trinidad and Tobago (50), and Jamaica (49) had significantly higher median ages than those from the Dominican Republic (44) and Haiti (46). Cuban immigrants also were much less likely to be of working age (68 percent) than other Caribbean immigrant groups that more closely resembled the overall foreign-born population.

Table 3. Age Distribution by Origin, 2014

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2014 ACS.

Caribbean immigrants have lower levels of educational attainment compared to the overall foreign- and native-born populations. In 2014, 20 percent of Caribbean immigrants (ages 25 and over) had a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 29 percent of the total foreign-born population and 30 percent of the U.S.-born population. Across Caribbean immigrant groups, Dominican (15 percent) and Haitian (16 percent) immigrants were the least likely to be college graduates, while immigrants from Jamaica (24 percent) and Trinidad and Tobago (26 percent) were the most educated, although their college-educated shares were still lower than that of immigrants overall.

Caribbean immigrants participate in the labor force at a similar rate as the overall immigrant population and a higher rate than the native born. In 2014, about 66 percent of Caribbean immigrants and immigrants overall (ages 16 and over) were in the civilian labor force, compared to 62 percent of the native born. Cuban immigrants had the lowest labor force participation rate (58 percent) among all Caribbean groups partly due to a higher share of elderly immigrants among Cubans in the United States.

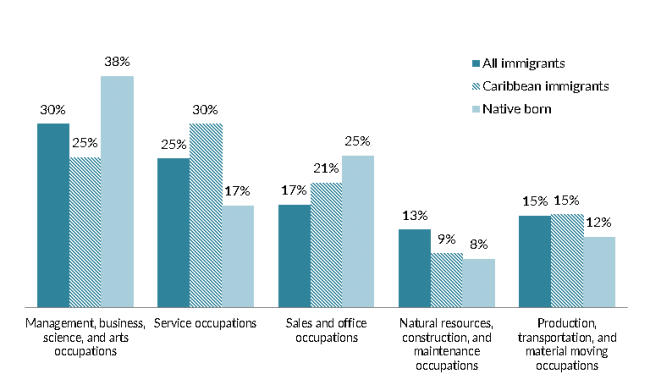

Compared to immigrant workers overall, Caribbean immigrants were more likely to be employed in service occupations (30 percent); sales and office occupations (21 percent); and less likely to be in management, business, science, and arts occupations (25 percent) and natural resources, construction, and maintenance occupations (9 percent). Consistent with their higher levels of English proficiency and educational attainment, immigrants from Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago were more likely than Caribbean immigrants overall to be in management, business, science, and arts occupations (32 percent and 37 percent, respectively). Immigrants from the Dominican Republic and Haiti were more likely to be employed in service occupations (33 percent and 41 percent, respectively).

Figure 4. Employed Workers in the Civilian Labor Force (Ages 16 and Older) by Occupation and Origin, 2014

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2014 ACS.

Income and Poverty

Caribbean immigrants had lower incomes compared to both the total foreign- and native-born populations. In 2014, the median household income among Caribbean immigrants was $41,000, compared to $49,000 for all immigrant households and $55,000 for U.S.-born households.

Caribbean immigrants were more likely to be in poverty than the U.S. born. In 2014, 20 percent of Caribbean immigrants lived in poverty, compared to 15 percent of the U.S. born and 19 percent of the overall foreign born.

Among all Caribbean immigrants, those from Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago had higher median household incomes ($51,000 and $52,000, respectively) and lower poverty rates (13 percent and 15 percent, respectively), while Cuban immigrants ($36,000 and 22 percent in poverty) and Dominican immigrants ($34,000 and 26 percent) fared the worst.

Immigration Pathways and Naturalization

Caribbean immigrants were much more likely to be naturalized U.S. citizens than the overall immigrant population. In 2014, 58 percent of the 4 million Caribbean immigrants residing in the United States were naturalized citizens, compared to 47 percent of all foreign-born individuals. Jamaican immigrants had the highest naturalization rate (66 percent), followed by those from Trinidad and Tobago (63 percent). Dominican immigrants had the lowest rate (52 percent), while Cubans (57 percent) and Haitians (56 percent) fell in between.

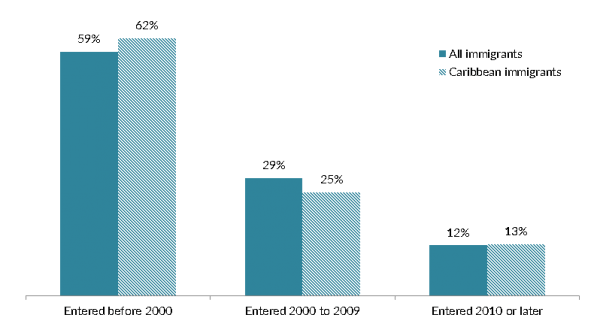

The period of arrival of Caribbean immigrants roughly mirrored the trend of the overall immigrants in the United States, with slightly more Caribbean immigrants entering before 2000 (62 percent, see Figure 5). Less than 10 percent of immigrants from Jamaica (9 percent) and Trinidad and Tobago (6 percent) arrived between 2010 and 2014. In contrast, 14 percent to 15 percent of Dominican and Cuban immigrants arrived during this period.

Figure 5. Caribbean Immigrants and All Immigrants in the United States by Period of Arrival, 2014

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2014 ACS.

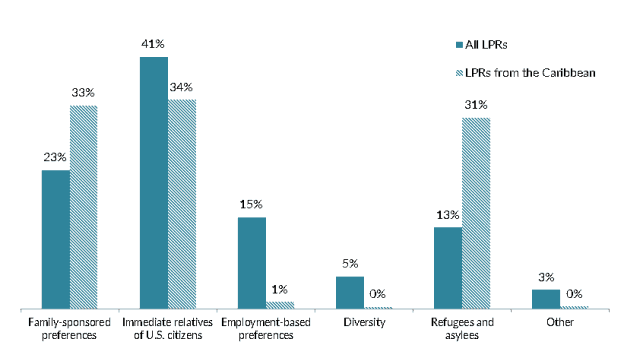

Overall, the majority of the 134,000 Caribbean immigrants obtained green cards (i.e., became lawful permanent residents [LPRs]) in FY 2014 did so through three channels: as immediate relatives of U.S. citizens (34 percent), through family-sponsored preferences (33 percent), or as refugees or asylees (31 percent), as shown in Figure 6. As a result of the Cuban Adjustment Act, Cuba accounted for the majority (96 percent) of refugee and asylee flows from the region.

Figure 6. Immigration Pathways of Caribbean Immigrants and All Immigrants in the United States, 2014

Notes: “Family-sponsored” includes adult children and siblings of U.S. citizens as well as spouses and children of green-card holders. “Immediate relatives of U.S. citizens” includes spouses, minor children, and parents of U.S. citizens. “Diversity” refers to the Diversity Visa Lottery program established by the Immigration Act of 1990 to allow entry to immigrants from countries with low rates of immigration to the United States. While many Caribbean nationals are eligible for the DV-2016 lottery, others are not (i.e., Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, and Great Britain dependent areas, which include Anguilla, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Montserrat, and Turks and Caicos Islands).

Source: MPI tabulation of data from Department of Homeland Security (DHS), 2014 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (Washington, DC: DHS Office of Immigration Statistics, 2016), available online.

Approximately 232,000 unauthorized Caribbean immigrants resided in the United States in the 2010-14 period, representing 2 percent of the total 11 million unauthorized immigrants, according to MPI estimates. The Dominican Republic (98,000), Jamaica (59,000), and Haiti (7,000) were the leading origin countries of unauthorized immigrants from this region.

Furthermore, as of 2016, an estimated 13,000 unauthorized youth from the Dominican Republic and 9,000 from Jamaica were eligible for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) deportation-relief program announced in 2012. As of March 31, 2016 (the most recent data available), 4,155 unauthorized youth from Jamaica, 3,463 from the Dominican Republic, and 2,908 from Trinidad and Tobago had applied for the program. A total of 3,298 petitions from DACA-eligible youth from Jamaica, 2,907 from the Dominican Republic, and 2,480 from Trinidad and Tobago had been approved, respectively.

Click here for two interactive data tools showing estimates of DACA-eligible unauthorized immigrant youth for top states and counties and application rates by country of origin.

Health Coverage

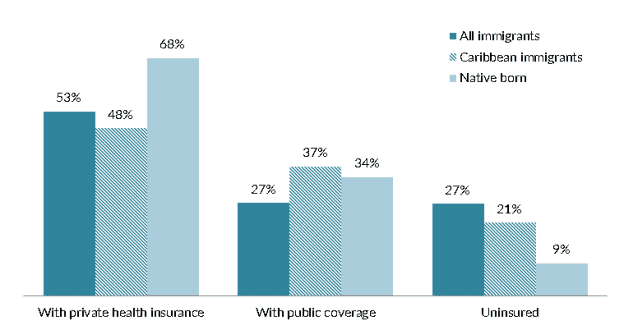

Caribbean immigrants in 2014 were less likely to be uninsured (21 percent) than the overall foreign-born population (27 percent). Caribbean immigrants were more likely to have public health insurance than the overall immigrant population, but less likely to have private coverage (see Figure 7). While the overall coverage rates among Caribbean immigrants groups remained roughly the same, the source of coverage differed: More than 40 percent of Cuban immigrants (40 percent) and Dominican immigrants (46 percent) had public health insurance coverage, whereas more than 60 percent of immigrants from Jamaica (61 percent) and Trinidad and Tobago (64 percent) had private coverage.

Figure 7. Health Coverage for Caribbean Immigrants, All Immigrants, and the Native Born, 2014

Note: The sum of shares by type of insurance is likely to be greater than 100 because people may have more than one type of insurance.

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2014 ACS.

Diaspora

The Caribbean diaspora population in the United States is comprised of approximately 6.7 million individuals who were either born in the Caribbean (excluding those born in the Caribbean to at least one U.S.-born parent) or selected a U.S. Census-designated Caribbean country or “West Indian” in response to questions on ancestry, according to tabulations from the U.S. Census Bureau pooled 2010-14 ACS.

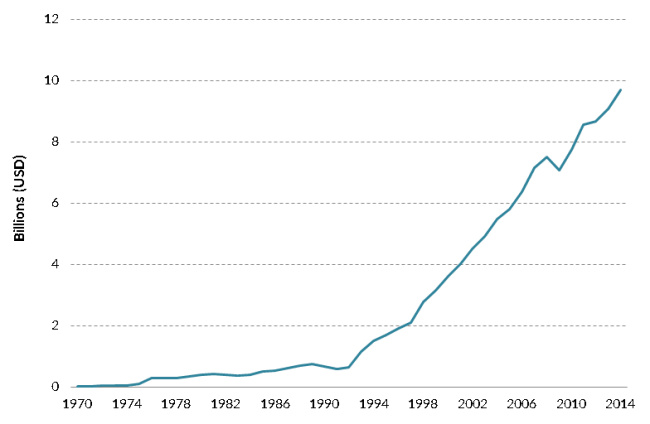

Remittances

Global remittance flows to the Caribbean region have increased greatly in recent decades. In 2014, total remittances sent to the Caribbean via formal channels amounted to $9.7 billion, representing about 8 percent of the sum of gross domestic product (GDP) in this region, according to World Bank data. (Note: data are not available for some countries in the Caribbean, most notably Cuba, which received an estimated $1.4 billion from Cubans in the United States in 2015.)

Figure 8. Annual Remittance Flows to the Caribbean, 1975 to 2014

Note: Due to limited data availability, this figure only includes remittance flows for Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Barbados, Curacao, Dominica, the Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, Sint Maarten, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Source: MPI tabulations of data from the World Bank Prospects Group, “Annual Remittances Data,” updated April 2016, available online.

Visit the MPI Data Hub collection of interactive remittances tools, which track remittances by inflow and outflow, between countries, and over time.

Sources

Bryce-Laporte, Roy Simon. 1979. Introduction: New York City and the New Caribbean Immigration: A Contextual Statement. International Migration Review, 13 (2): 214-34.

Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics. Various years. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Washington, DC: DHS Office of Immigration Statistics. Available Online.

Gibson, Campbell and Kay Jung. 2006. Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850 to 2000. Working Paper No. 81, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, February 2006. Available Online.

Hamre, Jaimie. 2015. Cubans Protest New Ecuador Visa Regulation. Reuters, November 27, 2015. Available Online.

Hennessy-Fiske, Molly. 2015. New Wave of Cuban Immigrants Reaches U.S., but through Texas, not Florida. Los Angeles Times, November 25, 2015. Available Online.

Krogstad, Jens Manuel. 2016. Surge in Cuban Immigration to U.S. Continues into 2016. Pew Research Center, August 5, 2016. Available Online.

Portes, Alejandro and Ramon Grosfoguel. 1994. Caribbean Diasporas: Migration and Ethnic Communities. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 533: 48-69.

Renwick, Danielle, Brianna Lee, and James McBride. 2016. CFR Backgrounders: U.S.-Cuba Relations. New York: Council on Foreign Relations. Available Online.

Thomas, Kevin J.A. 2012. A Demographic Profile of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available Online.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2015. 2014 American Community Survey. American FactFinder. Available Online.

—. 2016. 2010-14 American Community Survey. Accessed from Steven Ruggles, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, and Matthew Sobek. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. Available Online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2016. Number of I-821D, Consideration of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals by Fiscal Year, Quarter, Intake, Biometrics and Case Status: 2012-2016 (March 31). Available Online.

World Bank Prospects Group. 2016. Annual Remittances Data. Updated April 2016. Available Online.

Wyss, Jim. 2016. Colombia Denies Airlift for Cuban Migrants, to Begin Deportations. Miami Herald, August 2, 2016. Available Online.

Source: Migration Policy Ins